…The Canadian Coast Guard College Experience with Competency-Based Training

Introduction

The Canadian Coast Guard College (the College) is a national training facility for the Canadian Coast Guard. Training programs available at the College include a four-year Coast Guard Officer Training Program (leading to a Bachelor degree in Nautical Sciences awarded in partnership with Cape Breton University) and several specialized (short-term) professional development courses in Search and Rescue (SAR), Environmental Response (ER), radio operations and marine equipment maintenance and repair. While most of the training programs offered at the College were developed years ago through thorough needs assessments and task analysis, cutbacks in the 1990s combined with increasing pressures to deliver more courses created a situation where changes were made to training program without first conducting the costly and time-consuming needs assessment and task analysis. Over time, many of the College’s courses became somewhat out-of-sync with the operational needs of the Canadian Coast Guard. By the time it became obvious that training programs needed to be updated, employees having knowledge and experience of the original needs assessment/task analysis processes were long gone. For the last eight years, the College has been trying to gradually reinstate such processes.

This paper will present the competency-based approach that I have been developing and implementing at the Canadian Coast Guard College since 2001.

The Discovery of the Competency Profile

In January 2001, while working on a training renewal project for the Rescue Specialist program (Rescue Specialists being Coast Guard’s equivalent of paramedics), I stumbled upon a recently published document titled “National Occupational Competency Profile” (Paramedic Association of Canada, 2001). This document presents a listing of competencies for four levels of paramedical practitioners side-by-side. Within the document, competencies are organized using a four-level competency hierarchy consisting of 1) competency areas, 2) general competencies, 3) specific competencies, and 4) sub-competencies. Sub-competency statements are built from three elements: 1) a verb taken from a clearly defined list of cognitive, affective and psychomotor action verbs (see table 1) based upon Bloom’s taxonomy (Bloom, 1956), 2) a competency body, and 3) a performance environment (see table 2) describing where (or how) the competency must be demonstrated (see table 3 for a excerpt from a competency table). According to the document, “the work of developing Sub-Competencies is sometimes termed “curriculum blueprinting” because, in effect, it establishes the curriculum outline for a training program in terms of learning outcomes or enabling competencies” (Paramedic Association of Canada, 2001).

Table 1

|

||

|

COGNITIVE ACTIONS |

||

|---|---|---|

| Rank | Verb | Definition |

| 1 | List | To create a related series of names, words or other items. |

| 2 | Identify | To ascertain the origin, nature or definitive characteristics of an item. |

| 3 | Define | To state the precise meaning. |

| 4 | Describe | To give an account of, in speech or in writing. |

| 5 | Discuss | To examine or consider a subject in speech or in writing. |

| 6 | Organize | To put together into an orderly, functional, structured whole. |

| 7 | Distinguish | To differentiate between. |

| 8 | Explain | To make plain or comprehensible. |

| 9 | Apply | To prepare information for use in a particular situation. |

| 10 | Analyze | To separate into parts or basic principles so as to determine the nature of the whole; to examine methodically. |

| 11 | Solve | To work out a correct solution. |

| 12 | Modify | To change in form or character; to alter. |

| 13 | Infer | To reason from circumstances; to surmise. |

| 14 | Synthesize | To combine so as to form a new, more complex product. |

| 15 | Evaluate | To examine and judge carefully; to appraise. |

| AFFECTIVE ACTIONS Used to evaluate attitudes/beliefs in all Performance Environments (Not rank-ordered) |

||

| Assist | To give help or support. | |

| Choose | To select from a number of alternatives. | |

| Justify | To show to be reasonable. | |

| Receive | To acquire and accept. | |

| Acknowledge | To recognize as being valid. | |

| Value | To place worth and importance. | |

| PSYCHOMOTOR ACTIONS Used to describe skills in Performance Environments S and O (Grouped as Low, Medium and High complexity) |

||

| Low | Demonstrate | To show clearly and deliberately a behavior. |

| Low | Set-up | To gather and organize the equipment needed for an operation, a procedure, or a task. |

| Medium | Communicate | To convey information about; to make known; to impart. |

| Medium | Operate | To perform a function utilizing a piece of equipment. |

| Medium | Perform | To take action in accordance with requirements. |

| High | Adapt | To make suitable or to fit for a specific use or situation. |

| High | Adjust | To change so as to match, or fit; to cause to correspond. |

| High | Integrate | To make into a whole by bringing all relevant parts together. |

| Adapted from the Paramedic Association of Canada National Occupational Competency Profiles (Paramedic Association of Canada, 2001) | ||

Table 2

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competency area | General competency | Specific competency | Sub-competencies | PE* |

| Search and Rescue | Conduct maritime searches | Determine search areas | Define “Last Known Position” | A |

| Define “Datum” | A | |||

| Develop search plans | Synthesize a coastal search plan for the first vessel on-scene (assuming a drift of less than 6 hours) | S | ||

| Conduct maritime rescues | Develop rescue plans | List the elements of a rescue plan | A | |

| Discuss factors to be considered for each element of a rescue plan | A | |||

| Communications | Practice effective oral communication skills | Deliver an organized, accurate and relevant oral reports | List the components of effective oral communication | A |

| Describe the components of an oral report | A | |||

| Use appropriate terminology | S | |||

| Note. This table presents an excerpt from a competency table developed for lifeboat commanding officers.*PE = Performance Environment | ||||

Table 3

|

|

| Performance Environments | Definition |

|---|---|

| X | The employee should have a basic awareness of the subject matter of the competency. The employee must have been provided with or exposed to basic information on the subject, but evaluation is not required. |

| A | The employee must have demonstrated an academic understanding of the competency. Individual evaluation is required. |

| S | The employee must have demonstrated the competency in a simulated setting. Individual evaluation of physical application of skills is required, utilizing any of the following:

|

| O | The employee must have demonstrated the competency in a setting representative of the operational environment. Individual/team evaluation of physical application of skills is required. Alternate operational settings must be appropriate to the Specific Competency being evaluated. |

| Adapted from the Paramedic Association of Canada National Occupational Competency Profiles (Paramedic Association of Canada, 2001) | |

Since the Rescue Specialist program was in need of a task analysis, it was decided that one of the competency profile of the Paramedics Association of Canada could be used as a starting point. Coast Guard would simply have to add competencies specific to the Rescue Specialists to complete a full inventory of competencies for this program. From this full inventory, a complete training curriculum consisting of various off-the-shelf and in-house courses could be developed.

This initial work on the Rescue Specialist program eventually led to the development of a full competency-based training approach that would redefine how the College conducts needs assessments, task analysis, training development and training information management.

Competency Table, Task Analysis and Training Development

Before the adoption of the competency-based approach, the College usually attempted to develop new training based on a simple one-sentence client request (e.g., develop a one-week Pollution Response Officer course). Since such requests provided little information as to who would be the targeted learners and what competencies should the course provide, every course development project started with a task analysis. Client involvement in the development of such task analyses was typically minimal. The College was often put in a situation where it would have to make several assumptions (or leaps of faith in some cases) concerning target learners and course content. When prompted for input, most clients would provide a vague list of competencies that typically could not be taught in the timeframe originally requested. In an attempt to cover all required competencies, many instructors felt compelled to develop very dense courses that would expose learners to many topics too quickly and that would not allow learners to become truly competent.

Under the new competency-based approach, clients are now required to develop a full competency table before new training can be designed. The competency table development exercise is facilitated by College personnel but remains a client-driven process, with the resulting document being owned by the client.

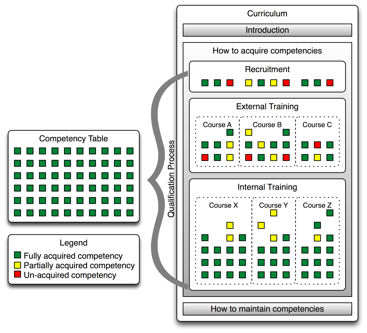

A qualification process is then developed from the competency table. This qualification process identifies how (or where) each competency will be acquired. Typical methods of acquiring competencies include recruitment processes (where employees are recruited with some of the desired competencies), external training and certifications, and in-house training. The complete sequence of recruitment activities and courses leading to a fully qualified employee will form the basis of the curriculum. The curriculum is developed through collaboration between the College and the clients. Figure 1 illustrates the relationships between competency table, qualification process, curriculum and courses.

Figure 1

Schematic representation of the relationships between a competency table, a qualification process and a training curriculum.

Under this new approach, program managers must determine what competencies are needed for the delivery of their programs while the College can focus on determining how best to develop training to teach targeted competencies effectively. Since the complexity of each competency is clearly established through the use of the verb taxonomy and through performance environments, timeframe constraints can be better addressed. Whenever a situation arises where there are too many competencies to cover for a given timeframe, the client will be required to revisit the qualification process. Options include removing some competencies from the requested course (this can be done by removing all competencies that are not absolutely necessary or by changing recruitment strategies to ensure that employees will have these competencies as a prerequisite to training), adjusting the complexity of the competencies to be covered in training (this is done by modifying the verb and/or performance environment), or acknowledging that the initial timeframe was inadequate. In a context where clients always expect more to be done with less, this process is proving to be incredibly useful in preventing the development of rushed learning activities that are not appropriately adapted to the complexity of the competencies to be acquired. Since the Coast Guard is involved in several high-risk operations, minimizing such learning activity/competency mismatches is crucial to employee safety.

Competency-Based Information Management

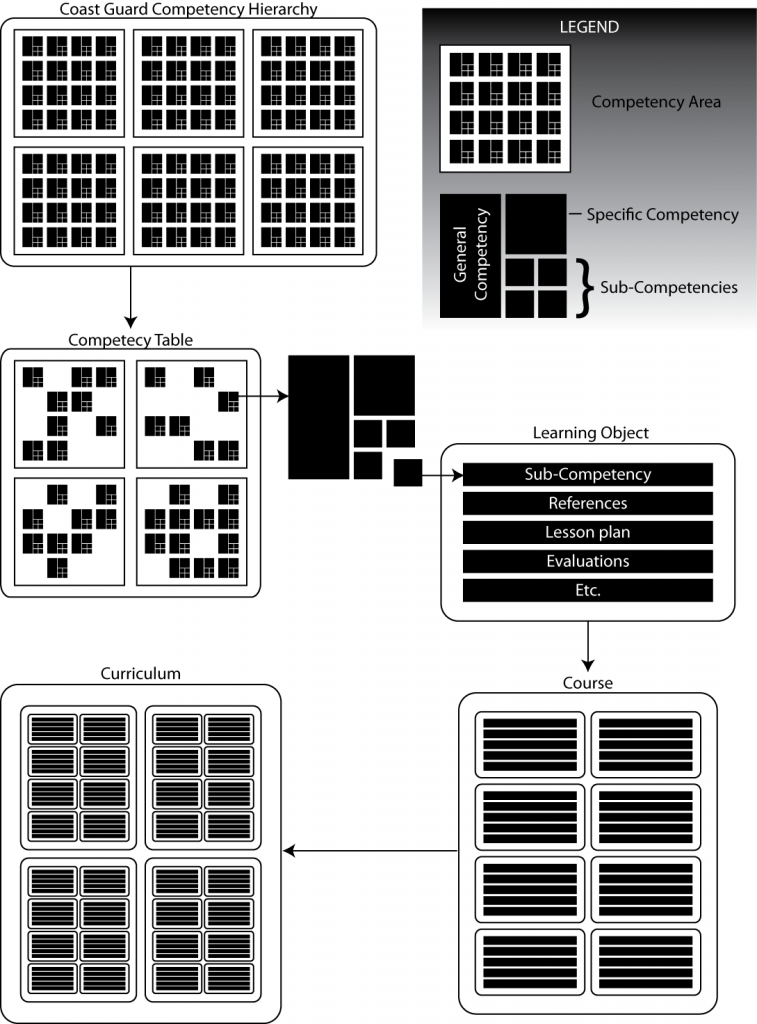

As I gained experience working with competency tables, it became obvious that many competencies will likely end up being reused within Coast Guard. All competencies pertaining to wearing the uniform, as an example, will be shared across all positions where employees have to wear the uniform. Sometimes the shared competencies will be identical; sometimes they may have similar competency body but may have different performance environments or different verbs. As an example, a Rescue Specialist may have “perform Cardio Pulmonary Resuscitation (CPR)” as a competency while the Rescue Specialist first aid instructor may have “evaluate CPR” as a competency. In this particular case, while the learning activities used to teach these competencies would differ (one being psychomotor and the other being cognitive), reference material (the CPR guidelines in the current example) is likely to be the same. If training has to be developed to teach shared competencies (e.g., “perform CPR”), it would be highly desirable, from an information management, standardization and cost effectiveness standpoint, to avoid developing multiples iterations of this training. Connecting the training documentation (including lesson plans, evaluations, reference material, etc.) to its associated competency could prevent such duplication of effort. Furthermore, to allow re-usability, training documentation must be somewhat self-contained and modular. Sub-competency statements, because of their close resemblance with learning outcomes, appeared to provide a logical foundation around which training documentation could be developed. While trying to find constructs to allow the modularization and re-usability of training, I discovered learning objects. Wiley describes learning objects as “small (relative to the size of an entire course) instructional components that can be reused a number of times in different learning contexts” (Wiley, 2000). Learning objects are typically associated with e-learning and are often developed with a course module as a core. I thus decided to adapt learning objects to my need by building them around sub-competencies and by making them generic (i.e., not necessarily designed for e-Learning). Under this approach, a course simply becomes a collection of learning objects brought together through a course training standard and presented in a logical sequence.

Based on this approach, it would be possible to build a repository of reusable and unique learning objects as new training is developed. It would also be possible, and highly desirable, to develop a repository of competencies from which new competency table could be built. As competency tables are developed for various Coast Guard jobs, we could organize competencies in an all-encompassing competency hierarchy. Under this system, a competency table would present a specific subset (applicable to a specific job) of the organization’s competencies. Figure 2 provides a schematic representation of the above concepts.

Figure 2

Schematic representation of the relationships from organizational competency hierarchy structure to curriculum.

These concepts were implemented in a database-driven tool designed to allow program managers to develop and manage their competency tables while also allowing training developers and instructors to create and manage learning objects, courses and curriculums. The tool has been built around a collaborative “wiki” web-based content management system called “Daisy” (see www.daisycms.org). Daisy, as an added benefit, provides a strong publication (html and PDF) engine, sophisticated versioning capabilities and powerful translation management tools. The first course to be fully developed on this system, using the competency-based approach described in this document, is presently being created and should be ready by March 2009. This course development process marks the first attempt at mapping Coast Guard’s competencies and will lead to development of the first competency-based learning objects.

Conclusions

The discovery of the Paramedic Association of Canada occupational competency profile and the subsequent development and implementation of the competency-based approach described in this paper is changing how the Coast Guard College approaches training development. It also raised the College instructor’s level of awareness concerning the selection of learning activities appropriately matched to the competency to be taught. These changes will ultimately lead to the development of better, more relevant courses.

While many systems exists to deliver training (and learning objects), the competency-based system that we developed as part of this project is the first of its kind as it allows authoring of competencies and associated learning objects collaboratively.

The concepts and tool developed in the last seven years could, if successful, be exported outside of the College, to the whole Coast Guard organization. All training development, whether done at the College or locally in the various Coast Guard regions, could be based on the concept of modular, reusable and competency-based learning objects. Such a widespread adoption the competency-based approach described in this paper would lead to dramatically improved use of training resources by ensuring that learning objects are developed only once and improved upon with time. In the next few months, the tool and associated concepts will be tested through various course development initiatives. If the tool works as designed and gain widespread adoption, it will completely transform how knowledge is managed within Coast Guard.

Author Note

Étienne Beaulé, Superintendent, Rescue, Safety and Environmental Training department, Canadian Coast Guard College.

I would like to thank Sandy Martin for her involvement in developing the first operational prototype of our competency management tool and Steven Noels, Marc Portier and Paul Focke for developing the database design and the final competency management tool.

References

- Bloom B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives, handbook I: The cognitive domain. New York: David McKay Co Inc.

- Paramedic Association of Canada. (2001). National occupational competency profile. Retrieved October 3, 2008, from http://www.paramedic.ca/Content.aspx?ContentID=4&ContentTypeID=2

- Wiley, D. A. (2000). Connecting learning objects to instructional design theory: A definition, a metaphor, and a taxonomy. In D. A. Wiley (Ed.), The instructional use of learning objects: Online version. Retrieved October 3, 2008, from http://reusability.org/read/chapters/wiley.doc

Colddiver's Designs

Colddiver's Designs